During the colonial era, Antigua was a heavily fortified naval and army base of operations in the West Indies for the British. English Harbour provided a deep natural harbour that was ideal for the refitting and sheltering of ships, and a Royal Naval Dockyard was constructed on its shores. This facility was intensively used during the Napoleonic Wars during which the British Navy and Army suffered huge losses due to tropical diseases and other illnesses. Loss of men due to disease was one of the highest for any military campaign at the time, and English Harbour was often referred to as the 'grave of the Englishman'.

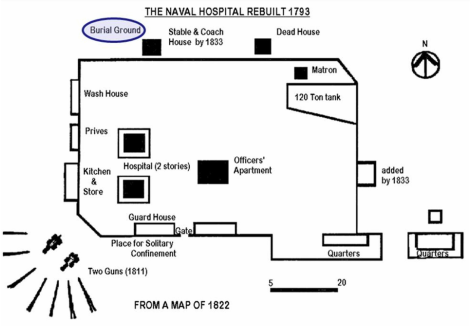

Historical records indicate that the hospital was open from A.D. 1793-1822, and may have provided care not only to naval personnel, but also to military personnel, slaves and the general public. While some records exist, most have been lost. Desmond Nicholson (deceased), then Director of the Museum at Nelson's Dockyard, has found many references to the hospital in various historical sources, including the following map of the hospital compound:

The majority of historic documents that have survived have not originated directly from the hospital but rather from a variety of sources such as parish baptismal records, correspondence between the Dockyard and Admiralty Office in London, slave registers, officer's logbooks and newspaper advertisements.

The site of a Naval Hospital (PAH-83) is located on a hill to the north of English Harbour. The entire area that the hospital and associated cemetery occupied is now a residential neighbourhood. In the past few decades, large portions of the site have been subject to considerable disturbance due to construction and landscaping developments. The undisturbed portions of the site are in imminent danger of destruction and this project seeks to salvage the remaining archaeological information.

After the study of the human remains is complete, the long-term plan for the remains is that they will be re-interred at a protected cemetery site such as one of the military cemeteries that are under the care of the National Parks Authority.

History of Research at PAH-83

In 1980, a midden associated with the hospital was discovered during contruction activities on the south-west side of the site, close to the former location of the main gate of the hospital compound. Salvage excavations were carried out by the Historical and Archaeological Society of Antigua and Barbuda, and reported on by Nicholson (1993).

Many interesting artefacts were found during these excavations, including fragments of European (median date of 1800) and Afro-Caribbean ceramics, wine and other bottles, pipes, and buttons not only British military and naval uniforms, but also from French military uniforms. One highlight is a shaker or hat badge from the 8th West Indies Regiment, which was one of a about a dozen regiments comprised of African slaves who were promised emancipation in return for 5 years of service. Another highlight was a ceramic pot and a mortar, both which contained powders that were analyzed and found to be substances that may have been used for medicinal purposes.

In 1997, test excavations were conducted by the students of the Antigua Field School under the direction of Reg Murphy. A single grave was found in the area of the cemetery, and subsequently excavated.

The Antigua Field School returned to the site in 1998 to begin multi-year archaeological investigation of the cemetery. This project is now in its fourth year. No excavations are planned for the 2002 season, however, they will likely resume in the 2003 fieldseason.

This project seeks to investigate life and death at the Dockyard through the analysis of human skeletal remains and mortuary practices in conjunction with evidence gathered from excavation of the hospital ruins and the remaining historical records.

Some Highlights of the Project (1998-2001)

Overall, 26 graves have been excavated yielding the remains of 31 individuals. All burials were simple, with most being in six-sided wooden coffins which were generally poorly preserved. With the exception of one coffin with swing bail handles, iron nails were the only coffin hardware found. In addition to burial in a coffin, two burials contained evidence of wrapping the corpse in a burial shroud. A brass shroud pin was found under the remains of a child, and the remains of an adult were found with scraps of textile and rope around his ankles.

Very few artifacts associated with the human remains have been found. Simple bone and shell buttons were the most common, but one burial also had brass buttons bearing a fouled anchor design that was common on the naval uniforms of lower ranking officers. The infant found in the double burial mentioned above had the remains of copper alloy beads around the neck and chest area.

Although historic records indicate that the hospital was only open for 30 years, the cemetery shows signs of heavy usage. Many of the graveshafts have been re-used, with or without disturbance to previous burials (some in a 'stacked' arrangement), or the graveshafts have overlapped upon one another.

Few markers exist at the cemetery site today, and those that remain are only the foundations for more elaborate structures. Long-time residents of the area tell of a time when many markers still stood, but they have since disappeared. Only one engraved marker remained a few years ago, at which time it was salvaged by the Dockyard Museum. It bore the following inscription:

Sacred

to the memory of

Mr. ALEXANDER BERNARD

late affistant surgeon of

H.M.S. Pyramus

who departed this life

on the 16th day of Oct 1821

aged 27 years

This stone is erected

in the memory of this Midshipman

of that ship

as a tribute of efteem

The human remains represent individuals that range in age from newborn to over 60 years, with a mean age in the early thirties. Individuals of both European and African/Afro-Caribbean ancestry are represented, with the latter comprising approximately 1/3 of the excavated individuals.

Children are represented by five individuals: two newborns, two infants (12 and 18 months old) and a three year old child. One of the newborns was interred in a grave with an adult male, and the two infants were buried in discrete graves in small coffins.

None of the adult individuals were female, however, only a small portion of the cemetery was excavated and there are no plans to return to the site.

Overall, the demographic profile of the cemetery appears to reflect that of the Dockyard and its support population in a general manner. While it was surprising to find individuals of different ancestry (European and African) in a cemetery of this era, historic records indicate that African and Afro-Caribbean slaves were owned and trained by the Navy to fulfil highly skilled occupations such as masons and sail-makers. These individuals comprised approximately 70% of the workforce in the Dockyard, were treated at the hospital. There is also one reference in a historic document to the baptism of the child of a slave taking place at the hospital. What are missing (or remain to be found) are historical documents that mention women being owned by the Navy or being treated at the hospital. As such, it is unclear whether the absence of female individuals from the exhumed assemblage is reflective of the past or not.

Investigations of the non-cemetery aspects of the site

In 1999, investigations expanded to include survey of the entire hilltop and test excavations around the remaining ruins of the hospital compound to assess the potential of the non-cemetery portion of the site. Ruins of the hospital compound wall and some other structures were located.

In 2000, as a follow up of the 1980 salvage recovery at the site the several 1m x 1m units were excavated to determine if the midden site. Intact material was indeed found in one of the units.

Historical records indicate that the hospital was open from A.D. 1793-1822, and may have provided care not only to naval personnel, but also to military personnel, slaves and the general public. While some records exist, most have been lost. Desmond Nicholson (deceased), then Director of the Museum at Nelson's Dockyard, has found many references to the hospital in various historical sources, including the following map of the hospital compound:

The majority of historic documents that have survived have not originated directly from the hospital but rather from a variety of sources such as parish baptismal records, correspondence between the Dockyard and Admiralty Office in London, slave registers, officer's logbooks and newspaper advertisements.

The site of a Naval Hospital (PAH-83) is located on a hill to the north of English Harbour. The entire area that the hospital and associated cemetery occupied is now a residential neighbourhood. In the past few decades, large portions of the site have been subject to considerable disturbance due to construction and landscaping developments. The undisturbed portions of the site are in imminent danger of destruction and this project seeks to salvage the remaining archaeological information.

After the study of the human remains is complete, the long-term plan for the remains is that they will be re-interred at a protected cemetery site such as one of the military cemeteries that are under the care of the National Parks Authority.

History of Research at PAH-83

In 1980, a midden associated with the hospital was discovered during contruction activities on the south-west side of the site, close to the former location of the main gate of the hospital compound. Salvage excavations were carried out by the Historical and Archaeological Society of Antigua and Barbuda, and reported on by Nicholson (1993).

Many interesting artefacts were found during these excavations, including fragments of European (median date of 1800) and Afro-Caribbean ceramics, wine and other bottles, pipes, and buttons not only British military and naval uniforms, but also from French military uniforms. One highlight is a shaker or hat badge from the 8th West Indies Regiment, which was one of a about a dozen regiments comprised of African slaves who were promised emancipation in return for 5 years of service. Another highlight was a ceramic pot and a mortar, both which contained powders that were analyzed and found to be substances that may have been used for medicinal purposes.

In 1997, test excavations were conducted by the students of the Antigua Field School under the direction of Reg Murphy. A single grave was found in the area of the cemetery, and subsequently excavated.

The Antigua Field School returned to the site in 1998 to begin multi-year archaeological investigation of the cemetery. This project is now in its fourth year. No excavations are planned for the 2002 season, however, they will likely resume in the 2003 fieldseason.

This project seeks to investigate life and death at the Dockyard through the analysis of human skeletal remains and mortuary practices in conjunction with evidence gathered from excavation of the hospital ruins and the remaining historical records.

Some Highlights of the Project (1998-2001)

Overall, 26 graves have been excavated yielding the remains of 31 individuals. All burials were simple, with most being in six-sided wooden coffins which were generally poorly preserved. With the exception of one coffin with swing bail handles, iron nails were the only coffin hardware found. In addition to burial in a coffin, two burials contained evidence of wrapping the corpse in a burial shroud. A brass shroud pin was found under the remains of a child, and the remains of an adult were found with scraps of textile and rope around his ankles.

Very few artifacts associated with the human remains have been found. Simple bone and shell buttons were the most common, but one burial also had brass buttons bearing a fouled anchor design that was common on the naval uniforms of lower ranking officers. The infant found in the double burial mentioned above had the remains of copper alloy beads around the neck and chest area.

Although historic records indicate that the hospital was only open for 30 years, the cemetery shows signs of heavy usage. Many of the graveshafts have been re-used, with or without disturbance to previous burials (some in a 'stacked' arrangement), or the graveshafts have overlapped upon one another.

Few markers exist at the cemetery site today, and those that remain are only the foundations for more elaborate structures. Long-time residents of the area tell of a time when many markers still stood, but they have since disappeared. Only one engraved marker remained a few years ago, at which time it was salvaged by the Dockyard Museum. It bore the following inscription:

Sacred

to the memory of

Mr. ALEXANDER BERNARD

late affistant surgeon of

H.M.S. Pyramus

who departed this life

on the 16th day of Oct 1821

aged 27 years

This stone is erected

in the memory of this Midshipman

of that ship

as a tribute of efteem

The human remains represent individuals that range in age from newborn to over 60 years, with a mean age in the early thirties. Individuals of both European and African/Afro-Caribbean ancestry are represented, with the latter comprising approximately 1/3 of the excavated individuals.

Children are represented by five individuals: two newborns, two infants (12 and 18 months old) and a three year old child. One of the newborns was interred in a grave with an adult male, and the two infants were buried in discrete graves in small coffins.

None of the adult individuals were female, however, only a small portion of the cemetery was excavated and there are no plans to return to the site.

Overall, the demographic profile of the cemetery appears to reflect that of the Dockyard and its support population in a general manner. While it was surprising to find individuals of different ancestry (European and African) in a cemetery of this era, historic records indicate that African and Afro-Caribbean slaves were owned and trained by the Navy to fulfil highly skilled occupations such as masons and sail-makers. These individuals comprised approximately 70% of the workforce in the Dockyard, were treated at the hospital. There is also one reference in a historic document to the baptism of the child of a slave taking place at the hospital. What are missing (or remain to be found) are historical documents that mention women being owned by the Navy or being treated at the hospital. As such, it is unclear whether the absence of female individuals from the exhumed assemblage is reflective of the past or not.

Investigations of the non-cemetery aspects of the site

In 1999, investigations expanded to include survey of the entire hilltop and test excavations around the remaining ruins of the hospital compound to assess the potential of the non-cemetery portion of the site. Ruins of the hospital compound wall and some other structures were located.

In 2000, as a follow up of the 1980 salvage recovery at the site the several 1m x 1m units were excavated to determine if the midden site. Intact material was indeed found in one of the units.